A Serendipitous Discovery of Gratitude, Vulnerability, & Strength.

By Sushmina Baidya, Regional Manager for Asia/Oceania

I looked at the magnificent Tower Bridge standing tall in the heart of London, and I thought to myself as the tower radiated its light into the water, “Does the tower realize that when the light decides to shimmer, the water looks more beautiful? Just like that, does a person’s individuality architect their ability to make decisions, recognizing their agency, that affects the lives of others?”

I immediately think of my own individuality and how it paved the way to carve my own agency. But is it always easy to recognize your agency? What do you even call an agency?

I was born and raised in a family of five in Nepal. My life until 16 was strictly regimented: driven to school at 9 AM, picked up at 4 PM, and expected to resume school assignments by 5 PM. Weekends were no different, and I often looked out my window, wondering if life had more to offer.

When I was 16, my school introduced a policy to reshuffle students based on academic scores, aiming to enhance performance in the School Leaving Certificate (SLC) exams. These exams were pivotal, with merit or distinctions leading to direct entry to Nepal’s finest colleges and additional scholarships. The pressure to excel was immense, and my family held high expectations, providing me with after-school tutoring and a study timetable.

The education system’s rigidity, focused on rote learning, led to a competitive environment where students were more concerned with memorizing content than understanding it. This pressure often resulted in stress, anxiety, and even suicide among students.

Schools, including mine, saw the SLC exams as an advertising opportunity. The National SLC Topper would be awarded accolades, newspaper coverage, and national recognition every year. Only one student would be awarded as the National SLC Topper. My school wanted that student to represent them, leading to the introduction of the reshuffling policy and special tutoring for selected students. This approach overlooked the students’ individual needs and mental well-being, reflecting a broader failure in the education system. I felt angry, frustrated, and tired of the tyranny of our school.

How does an educational institute, that holds the future of students decide so easily, that only specific students are worthy of additional support?

When students were already vulnerable amidst the need to validate their self-worth for an examination, aren’t schools supposed to support them, if not able to change the larger educational system?

The next day, I helped orchestrate a series of silent protests following the proposals to reshuffle the students. For three days, the students refused to relocate to their new section. The teachers were not allowed to enter the classrooms and continue teaching. It was our conscious actions demanding that the school administrators revisit the policy. Our peaceful protests echoed the truth of the structured oppressive system of the school. Our protests were infused with rage, fear, and hope directed toward change. Our screams of protest were euphonious chimes of a grandfather clock that indicated midnight — a start of a brand new day, and a hope for change.

After three days of successful protests, the school decided to ban the policy. The school announced that all students will receive tutoring regardless of the scoresheet. The policy to reshuffle the students was dismissed. The announcement occurred in an auditorium hall with all the students anxiously awaiting the final decision. When the policy was dismissed, the crowd had tears of joy and excitement.

For me, as a 15-year-old at the time, it was the first time I had felt heard. It was not only because the school lifted the policy but the collective efforts of my friends that made my 15-year-old self feel recognized. At that moment, I realized two very important lessons.

- An act of conscious effort nourishes each individual, uplifts each other, and awakens people to their abilities to decide.

- Fear is a strength that enables a person to step away from oppression. The protest would have invited repercussions, but nothing felt more important than the evocative image of the oppressive education structure and the students who suffered from it.

This incident left me feeling grateful. I was grateful that I could feel the power of resilience, love, and young people unapologetically demanding change. All the students showcased their individuality, and I began recognizing my own through it.

After the incident, I refused to stay confined between my life at home and school, a common restriction for women in Nepalese households. Growing up, I thought this confinement was for protection, but I later realized it reflected a male-domineering patriarchal society. Even as I fought back, I felt guilty for taking my stand. My work with youth-led organizations in Kathmandu supported me in moving forward, and after seven years, I became a fellow with Peace First in 2019. Two years in this role, witnessing the magic created by young people, led me to understand that my individuality was shaped by those around me. Whether it was the incident with my school, my efforts to free my mobility, or the stories of young people at Peace First, all of it contributed to my realization of what it means to recognize and practice agency.

At Peace First, young people actively engaged with their communities, understanding and exercising their agency. This understanding wasn’t solely derived from formal education but from meaningful interactions within their communities. Peace First saw thousands of youth demanding change and taking steps to achieve it. Projects like TransEnd in Bangladesh, advocating for the LGBTQI+ community, and Haritha Dwani in India, focusing on environmental conservation, were testaments to this youth empowerment. These initiatives were not just projects but voices of resilience, learning, and empowerment, showcasing how youth agency was being realized and practiced.

So, how does one recognize their agency? Who do we hold accountable and responsible for ensuring children and young people recognize their agency? How are projects led by young people at Peace First mean recognition of agency? Are projects the only way to determine their capability?

Amartya Sen’s Theory of Capability emphasizes that people’s abilities extend beyond mere commodities, focusing on their capacity to live fulfilling lives and contribute to societal well-being. The projects led by young people at Peace First reflect this theory, as they were conscious choices to address social justice and build resilience. These young individuals were not just passive recipients of freedom but active agents of change within their communities.

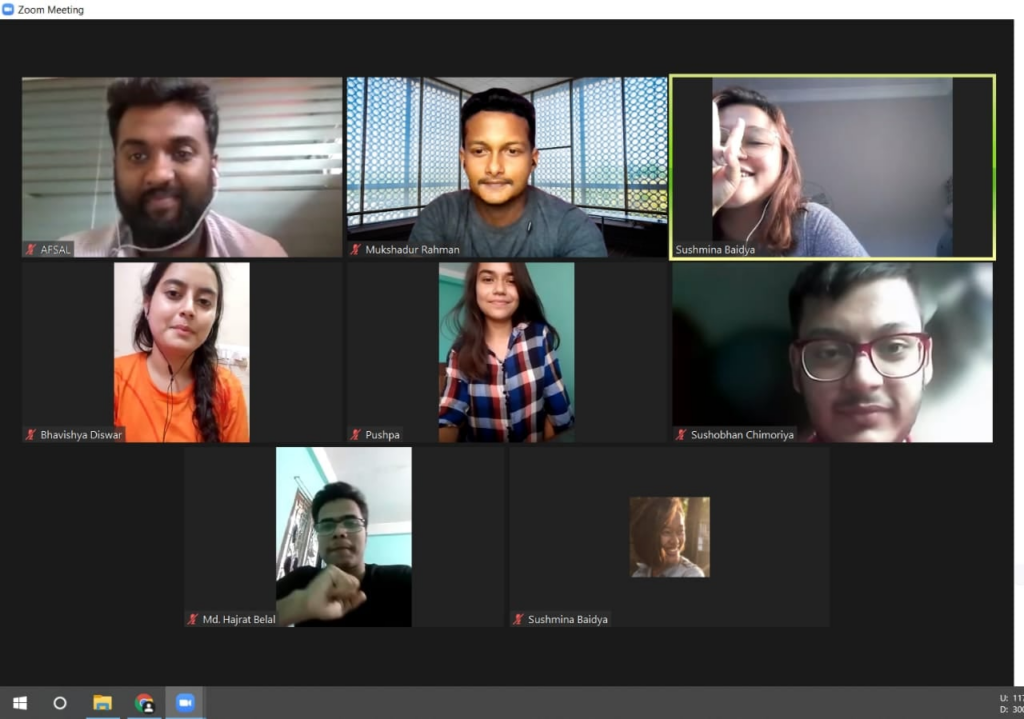

The agency of young people at Peace First was shaped not only by their projects but also by virtual communities, storytelling, and relationships within their communities. In 2020, while working with our ambassadors representing Asia, we brainstormed ways to enhance regional outreach. One idea was to partner with local organizations to provide mentoring, overcome language barriers, and strengthen local connections. This led to hundreds of new projects and fifteen receiving personalized mentoring, allowing young people, often excluded due to age bias, to actively participate and make collective decisions with their mentors.

Often, our society’s imperialist and patriarchal views prevent us from recognizing the agency of young people, seeing them as vulnerable. At Peace First, youth-led projects demonstrate that agency is more than a stand-alone concept; it’s intertwined with cultural shifts, removing age biases, and fostering intergenerational partnerships. My three years with Peace First have daily reinforced the importance of agency. By recognizing and integrating it into our practices, we pave the way for countless young leaders like Lamea and Prijin to lead change. What we need to do is recognize them.

At Peace First, I have had the opportunity to closely understand the implications of taking up leadership spaces, realizing one’s authenticity, and recognizing agency. This curiosity probably led me to study for my Master’s in Children, Youth, and International Development at the University of London.

So, at 27, when I stood in front of Tower Bridge, standing tall and proud in the heart of London, with lights reflected on the water and sublime stars shining in the sky, I felt a connection to its strength and capability. Just as the bridge and stars shine together, youth agency is about understanding competencies, embracing diversity, and fostering a space for thoughtful leadership and vibrant energy. This is how we, too, can shine together.